Cultural difference between countries and regions

EDUCATION

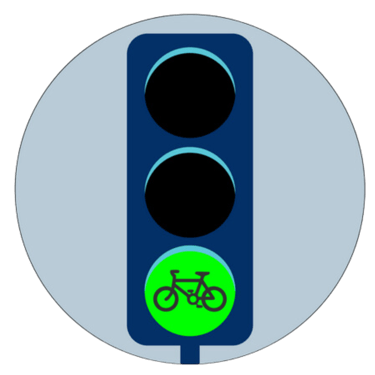

Immigrants in Europe often lack knowledge of the traffic rules, and etiquette and are less experienced in cycling than the locals. Therefore they are less likely to cycle daily and at a bigger risk of causing an accident when cycling. Female immigrants from the middle east and many other non-EU countries are even less likely to cycle, due to certain myths and cultural differences.

In recent years, the significance of integrating comprehensive cycling and traffic education into school curriculums has been widely acknowledged across many Western European countries. Nations like the Netherlands, Denmark, and Germany have long championed these programs, recognizing the dual benefits of promoting sustainable transportation and enhancing road safety. In stark contrast, southern and Middle Eastern countries often exhibit a notable deficiency in such educational initiatives.

Western European countries have established robust frameworks that embed cycling proficiency and traffic rules into early education. In these nations, children are taught from a young age not only how to ride a bike but also how to navigate roads safely, understand traffic signs, and adhere to the rules of the road. This early education fosters a culture of cycling and road safety that persists into adulthood. The extensive network of dedicated cycling paths, strict enforcement of traffic laws, and a societal emphasis on sustainable transportation further reinforce these practices. Consequently, cycling is viewed as a viable and safe mode of transport, significantly reducing traffic congestion and environmental impact.

Conversely, in many southern and Middle Eastern countries, the education system often lacks formalized programs focused on cycling and traffic safety. Several factors contribute to this gap, including differing cultural attitudes towards cycling, infrastructure limitations, and policy priorities. In many of these regions, cycling is often perceived more as a recreational activity rather than a primary mode of transportation. Moreover, the infrastructure necessary to support safe cycling—such as dedicated bike lanes and comprehensive traffic management systems—is frequently underdeveloped or absent altogether.

The absence of systematic cycling education in schools results in young people who are less aware of traffic rules and the benefits of cycling. This lack of awareness can contribute to higher rates of traffic accidents and a general reluctance to adopt cycling as a means of transport. Additionally, the car-centric nature of urban planning in these regions exacerbates traffic congestion and pollution, further deterring the adoption of cycling.

The contrast in educational approaches between Western European countries and their southern and Middle Eastern counterparts highlights the broader societal and infrastructural challenges that need to be addressed. Implementing comprehensive traffic and cycling education programs in southern and Middle Eastern countries could significantly enhance road safety and promote sustainable transportation practices. Such initiatives would require a concerted effort from policymakers, educators, and urban planners to reframe cycling as a practical and safe transportation option and to develop the necessary infrastructure to support it.

In conclusion, while Western European countries set a commendable example of integrating cycling and traffic education into their educational systems, southern and Middle Eastern countries lag behind. Bridging this gap requires not only educational reforms but also significant improvements in infrastructure and cultural attitudes towards cycling. By fostering a new generation of informed and responsible road users, these regions can look forward to safer, more efficient, and environmentally friendly urban environments.